By virtue of a strategic position – in the centre of an oasis of the same name and at the crossroads of several important routes connecting Iran, India and China – the city of Balkh (North Afghanistan) played a prominent role in the history of Asia. The city appears in Herodotus’ chronicles as Bactra, the capital of Bactria, a vast region known since the Bronze Age for its wealth and power and centered around the Oxus/Vakhsh River (Amu Darya). While no evidence has been found to confirm the legendary account of the Greek doctor and historian Ctesias († after 393 BCE) about Assyrian incursions in the 9th-8thcentury BCE, Bactria is listed in the Achaemenian royal inscriptions as one of the Satrapies of the Persian Empire. After the conquest by Alexander the Great and a short Seleucid interlude, in c. 250 BCE Bactria became an autonomous kingdom under Greek rulers who proclaimed their independence from the Seleucid Empire. In the mid 2nd century BCE Bactria was invaded by the Yuezhi, a confederation of nomadic tribes that, once settled there, made Bactria the first nucleus of the Kushan Empire, one of the largest and most powerful Asian kingdoms. In the mid 3rd century CE Bactria fell under Sasanian dominion. During the second half of the 4th century CE a new political and territorial situation was created by nomadic invasions, until the region passed into the hands of the Western Turks in the 6th century CE.

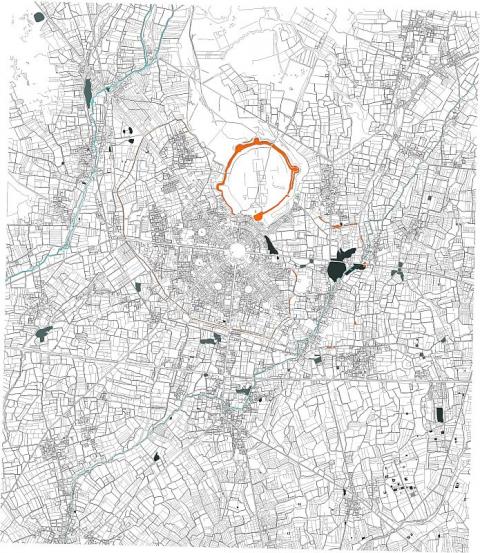

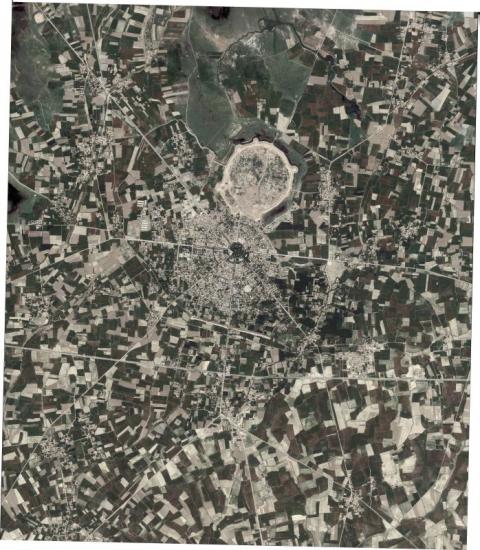

Despite the investigations carried out since 1920 by several national and foreign institutions, the enormous archaeological potential of Balkh remains only minimally realized, partly because it is buried under the modern town. The urban layout is partially known thanks to the remains of walls that, in different periods were built around the city and the citadel according to the extension of the city at that time. The citadel preserves stretches of the clay wall of the medieval period up to 20 m high, which partially cover the Greek one (Fig. A).

Important periods of the city’s history, such as the Achaemenid and the Greek, are mainly known from ceramic and numismatic finds. The coins, which attest to the presence of a mint at such an early date, confirm the political and cultural prestige of the city. Recent archaeological investigations being carried out by the Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA) are noticeably adding new facets to our scant knowledge. At Tepe Zargaran, an artificial mound enclosed within the Kushan period walls, Greek stone architectural elements have been found re-used there in a later context, and at Cheshme-e Shafar imposing remains of the Achaemenid period, including a gigantic stone structure that might be interpreted as a Zoroastrian fire altar, have been documented. As a matter of fact, a firm literary tradition indicates that Balkh was a stronghold of Zoroastrism, which was practiced side by side with other religions, first among them Buddhism. Other, less-known religious cults appear in significant Bactrian temples, for instance: the “Oxus Temple” at Takht-i Sangin (Tajikistan), probably dedicated to the deified personification of the Oxus River; the so-called “Temple of Dioscuri” at Dilberjin (Afghanistan), where it seems that a Central Asian goddess was venerated; and the famous bagolango ("temple" in Bactrian) of Surkh Kotal, consecrated to the personified “Victory” of the Kushan king Kanishka.