Butkara I (3rdcentury BCE – 10th century CE), identified as the splendid Tolo described by the Chinese pilgrim Songyun in the 6th century CE, was the long-lasting, major Buddhist sacred area of modern-day Swat (Khyber Pukhtunkhwa province, North-west Pakistan). Known in ancient times as Uddiyāna, this region was considered one of the most sacred locations of Buddhism. Important trade and pilgrimage routes traversed it at least until the 6th century CE, when most of the international traffic shifted towards Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the prestige of Uddiyāna’s Buddhism, which greatly contributed to the development of the esoteric Vajrayāna, did not vanish, and if we can trust the Tibetan tradition, Buddhism was introduced in Tibet by Padmasambhava, a famous master from Uddiyāna.

It is exactly from Butkara that in the 1950s the Italian Archaeological Mission of IsMEO (later IsIAO), under the leadership of Domenico Faccenna, began the archaeological investigation of Swat with the primary aim of re-discovering the reasons for the ancient fame of this land.

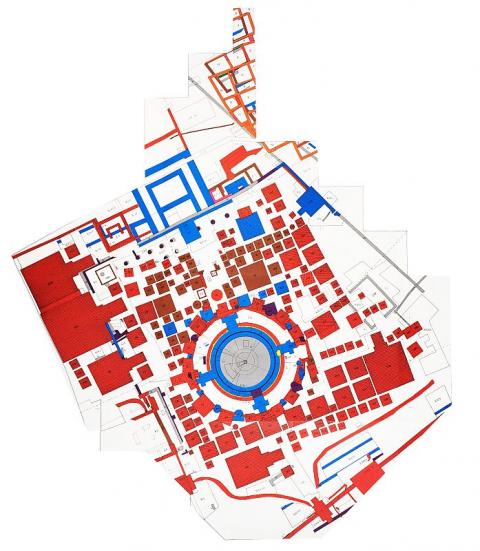

The core of the sacred area of Butkara I is the Great Stupa, which is surrounded by 227 minor monuments, such as shrines, small stūpas, and columns, of different periods (Fig. 4C). Four major phases of reconstruction, which progressively enlarged and enriched the Great Stupa, did not change the original circular plan, probably in order not to alter its venerable recognition as a “Dharmarājikastūpa”. This epithet, which is believed to denote a stūpa built by the emperor Aśoka (3rd century BCE), is indeed attested in two early inscriptions.

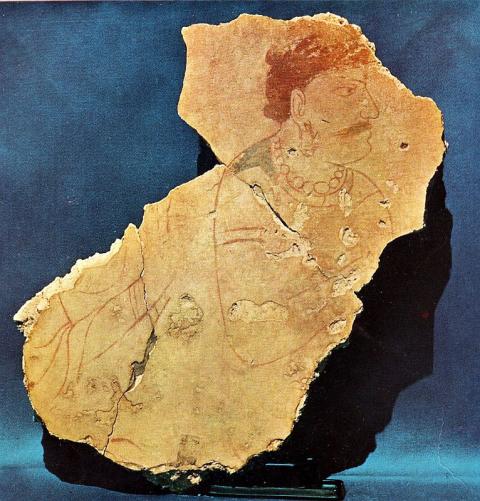

The great renewal and enhancement that occurred in the period of Great Stupa 3, probably during the time of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II at the turn of the 1st century BCE to 1st century CE, is of the utmost importance for the study of Buddhist art and architecture; it marks the beginning of the wide artistic phenomenon of Gandharan art that can be observed for the first time within a reliable archaeological sequence. Among the most significant results is the fact that the archaeological data shows that the very beginning of the figurative language of Gandharan art is decidedly more Indian than Hellenistic, contradicting the widespread notion of a purely Hellenistic outset progressively “corrupted” by Indian taste.

Of no lesser importance is the following period of Great Stupa 4 (Fig. 4C), which spans from c. 300 CE in to the 7th century CE. This period, which includes the time of the Huna dominion, is not only one of the longest in the life of the site; it is also one of the richest in terms of building activity and decorative embellishment, especially during phase 5 (5th to 7th century CE) of this period.