The Buddhist site of Tapa Sardar (near Ghazni, Afghanistan) lies on a hill overlooking the Dasht-i Manara plain along the ancient “Southern Route”, which still connects Kabul and Kandahar. Literary and archaeological evidence suggest that the sanctuary, built during the late Kushan period, was probably a royal foundation. The inscription on a pot reading Kanika mahāraja vihāra (“the temple of the Great King Kanishka”) might not refer to Kanishka I (c. 127/128–150/151 CE) but rather to Kanishka II (c. 231/232–243/244 CE) or Kanishka III (second half of the 3rd century); nevertheless, it is significant that this epithet is maintained in later names for the place such as Šāh Bahār (“the Temple of the King”) and the modern toponym Tapa Sardar (“the hill of the leader”). Indeed, the site is perhaps identifiable with the Šāh Bahār which, according to the Kitāb al-buldān (The Book of the Countries) by the Arab historian and geographer al-Ya'qubi († c. 897 CE), was destroyed by the Muslim army in 795 CE. From an archaeological point of view, the particular prestige of the site is shown by its visual prominence and monumentality as well as its complex artistic and architectural development. These features support the hypothesis that important religious and political ceremonies took place there.

The core of the site is the Great Stupa, which rises from the Upper Terrace surrounded by chapels and other small stūpas and cult statues. Additional sacred areas, probably also the monastery, were located on lower terraces.

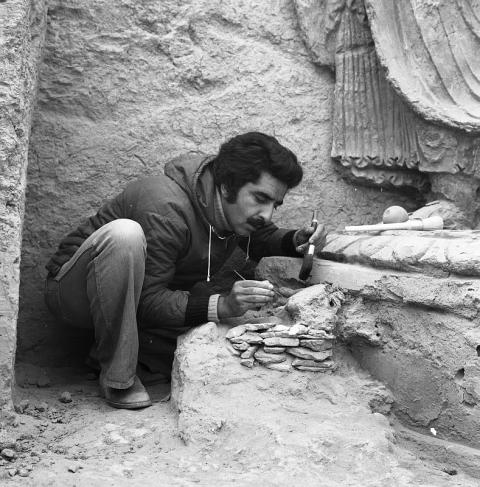

Apart from the Great Stupa and a few other monuments in stone, the primary building and decoration material was unbaked clay, and the plasticity and malleability of this material permitted the architects and sculptors nearly unlimited possibilities in producing their masterpieces. However, because clay is also so fragile, very little survives from the earliest phases of the site, which was destroyed by a fire usually attributed to the Muslim conquest of the area by 'Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad in 671/72 CE.

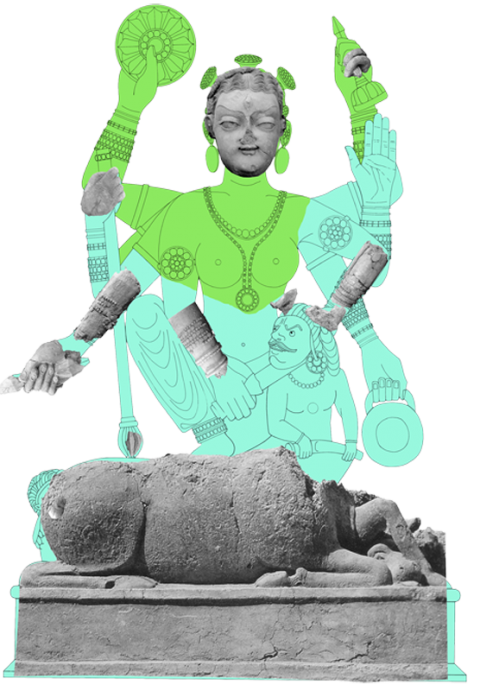

Nevertheless, a layer of filling partly formed by debris yielded hundreds of sculpture fragments, whose strong Hellenistic touches connect the early artistic production of Tapa Sardar (Antique Period 1) with the “Gandharan” mainstream of the first centuries CE. The following Antique Period 2 was characterized by the colossal size of the images and by an extensive use of gilding in their decoration. The Recent Period, stylistically very close to Fondukistan, exhibits signs of an extraordinary revival which followed the earlier destruction. During this period the chapels were built and lavishly decorated with sculptures and paintings reflecting major issues in the religious culture of the time: the transcendent nature of the Buddha; the 'death' (nirvāṇa) of the historical Buddha; the waiting for the future Buddha Maitreya; and the fundamental role of the king as guardian of the Buddhist doctrine in the time between the past and future Buddha.

.jpg%3Fitok=nd0ZNTVJ)