Nevertheless, this peace between the Chionites and Shapur was short-lived, since heavy fighting in the East broke out during the last 15 years of Shapur's reign. At this time a Sasanaian mint was set up south of the Hind Kush, probably in Kabulistan, in order to secure the payment of troops in the area. Bactria was finally given up to the Kidarites (showcase 3), who originated from among the Chionites, while south of the Hindu Kush Kabulistan fell around 385 CE to a second Hunnic group, the Alkhan (see showcase 6).

Around 467 CE Peroz (457–484 CE) again brought Bactria under Sasanian control (No. 7 and showcase 3, No. 8); however, shortly thereafter the king lost his life in battle against a new Hunnic power, the Hephthalites (see showcase 10). The empire fell into internal crisis after this catastrophe, and the Sasanian were forced to purchase peace with the Hephthalites by paying a high tribute. Only after Kawad I (488–496; 499–531 CE) had regained the throne with Hephthalite assistance could the internal situation be stabilized. In 502 CE he felt powerful enough to launch a new offensive in Armenia against the Byzantine emperor Anastasuis (491–518 CE) (see showcase 1, No. 8) but, as is often the case, without lasting territorial gain.

The Sasanian empire moved toward a new high point under Kawad's son Khusro I (531–579 CE), who received the by-name "of immortal soul" (No. 9). He found an equal opponent in the emperor Justinian I (527–565 CE) (see showcase 1, No. 13). Beginning in 540 CE both empires stood face-to-face on various battlefields in the Levant and Syria after a Goth embassy had tried to encourage Khusro to enter in war against Justinian. Khusro then turned his attention again to the East, where in Northeast Asia a new nomad power, the Western Turks, had pushed up to the borders of the Hephthalite kindgom around the middle of the 6th century. With diplomacy Khusro managed to forge an alliance with the Western Turks, which ultimately brought down the once powerful Hephthalite kingdom. The Turks successively extended their area of rule westward into the area around lower Volga River and established themselves as an important new factor between Byzantium, Persia and China.

In 568 CE a diplomatic embassy from the Turkic khagan Sizabul, which also included a delegation of Sogdian merchants, arrived at the court of the Byzantine emperor Justin II (565–578 CE) with an offer of alliance and peace. On the way the embassy had been received in Ctesiphon at the court of Khusro I (No. 9), who had rejected their wish to open the Iranian markets to Sogdian silk merchants. Byzantium was not opposed to the Turks' offer, increasing for the Sasanians the danger of a two-front war, which then broke out in 572/3 CE. Khurso emerged as the winner, raising the Sasanians again to the indisputable number one of the political world stage. Conflicts within the leading Western Turkic elite finally allowed Sasanian troops under the command of Wahram Chobin to push deep into Turkic territory in 588/89 CE, temporarily putting a hold on the Turkic threat.

The last military triumphs took place during the reign of Khusro II (590–628), the grandson of Khusro I who ascended to the Sasanian throne as legitimate "King of Kings" only with the help of the Byzantine emperor Maurice (582–602 CE). After Maurice had fallen victim to a coup lead by Phocas (602–610 CE), Khusro decided to defeat Byzantium once and for all. After Jerusalem had been plundered and the Holy Cross brought to Ctesiphon in 614 CE, Egypt was conquered in 619 CE and, finally, in 626 CE the Sasanian army together with Avar troops stood before the gates of Constantinople. In return, Heraclius (610–641 CE) (showcase 1, No. 14), who had been elevated to emperor following the removal of Phocas, destroyed the Sasanian fire temple at Takht-e Suleyman ("Throne of Solomon", south east of Tabriz, NW Iran) in 623 CE and decisively defeated them in Mesopotamia in 627 CE. The Western Turks also joined in the war on the Byzantine side and occupied the Transcaucasus. Unable to escape this situation, the powerful men of the empire refused their allegiance to Khusro II; he was deposed and killed in 628 CE.

The Sasanian empire thereafter sank in internal conflict over the throne and thus became easy prey for the Muslim invaders, who, united under the new religion Islam, conquered the entire Near East and Iran in less than 20 years after the death of the prophet Mohammad in 632 CE. Even the Byzantine victors could not hold back the Muslim expansion and lost their entire eastern provinces. The Turks did not fare much better; they were also caught up in internal conflicts and became easy prey to the expansionist politics of the new Tang dynasty in China.

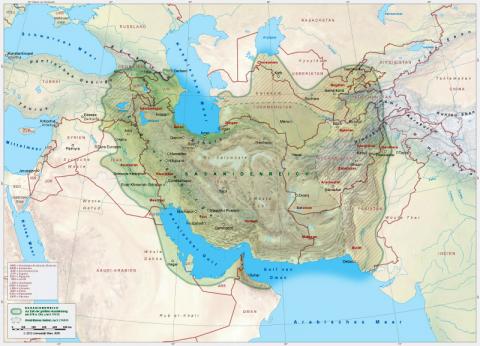

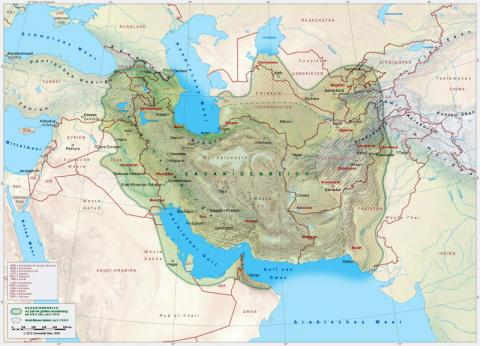

Despite all the political crises, the Sasanian monetary system based on the silver drachm proved to be exceedingly stabile and is evidence of a well-organized administrative system and prudent economic policy. Mints were distributed throughout the entire empire, thereby ensuring the local supply. Along international trade routes, over land and by sea, Sasanian coinage reached into Central Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, India, Ceylon and China. In Central Asia the Sasanian drachm became the model for numerous local coinage systems, among them those of the Huns and Western Turks. Even the new Arab rulers held on to the Sasanian drachm for half a century before creating their own coinage (showcase 16).

The crowned image of the Sasanian "King of Kings" together with the fire altar – a symbol of the Zoroastrian religion and of the royal fire lit at the ascension of each king – became a universally valued trademark which remained largely unchanged for centuries. The inscriptions are composed in Sasanian Middle Persian (Pehlevi) and give the name and title of the king, who presents himself as His "Mazda-worshipping Lord, King of Kings of the Iranians and Non-Iranians, whose lineage (image/glory) is from the Gods". The legends on the reverse label the fire with the name of the respective king. Later the titles are shortened, and the year of the king's reign and the mint are given on the reverse.