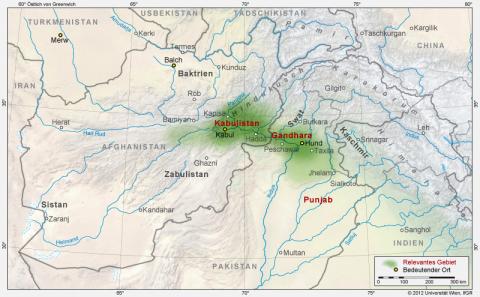

The coins of the Hindu Shahis display in the obverse a left-facing bull, the companion of the Hindu god Shiva; on the reverse is a rider carrying a lance with a flag (Nos. 1, 2). The inscriptions, composed in Brahmi, record various titles such as "Spalapati" (military commander) or "Samanta". The individual names of the specific rulers, as are known from written sources, are not given on the coins, making their attribution to the various kings nearly impossible. Kabul and Udabhandrapura in Gandhara are possible mints. The exceedingly rich silver coinage of the Hindu Shahis was most likely enabled largely from the silver mines of the Panjshir Valley (150 km north of Kabul). With the loss of Kabul to the Saffarids, Islamic coinage is documented there beginning in 872 to 883 CE. The first Samanid dirhams from the Panjshir valley are dated 293 AH (= 905 CE). The incorporation of Afghanistan in the Islamic world was thus completed fully and permanently. Nevertheless, the small kingdom in the Hindu Kush had successfully defended itself against Arab expansion for 250 years.

Following the death of the prophet Mohammad in 632 CE, the Arabs, carried by their new religion Islam, set out to conquer Byzantine Syria, Palestina, Egypt and North Africa, which they accomplished within a few years. The conquest of the Persian empire of the Sasanians, who had ruled Iran for over 400 years, was essentially completed in 651 CE. The last Sasanian king, Yazdgerd III (632–651 CE), was killed in Merv as the royal family fled into exile at the Chinese court.

The first Muslim ruling dynasty, the Umayyads (651–750 CE) belonged to the same tribe as the prophet Mohammad (Nos. 11, 12), and they established the capital of the Caliphate in Damascus. In 750 CE the Umayyads were ousted by the Abbasids, and the capital of the Islamic empire was moved to Baghdad in 762 CE (No. 13).

Early Islamic coinage was modeled on the existing monetary structures found in the conquered regions: in former Byzantine Syria and Palestine copper coinage was struck following the Byzantine model (No. 5). In the year 74 AH (693/694 CE) a remarkable new type of coin began to be struck with an image of the standing caliph on the obverse; he wears a belt and sword and is represented in the pose of a prayer leader (No. 6).

In the former Sasanian empire, Mesopotamia and Iran, the Sasanian silver drachm of Khusro II (r. 590-628 CE) served as the model for the coinage of the Arab governors. While the images matched the Sasanian prototype, an Arabic inscription, "In the Name of God", was added to the border and the name of the Sasanian king was replaced by that of the caliph or governor (Nos. 7–10). However, the Sasanian blessing in Middle Persian remained.

This kind of fragmented coinage inspired by ideas foreign to Islam was no lasting solution for the young Muslim empire. Thus in 77 AH (696/697 CE) caliph 'Abd al-Malik (685–705 CE) instituted a comprehensive reform that gave the new coins an unmistakably Islamic appearance (Nos. 11–13). Religious inscriptions with citations from the Koran replaced images and were complemented by administrative information such as the mint and year of issue (AH). Even the name of the ruler was left out, since the coins were struck "In the Name of God". Only under the Abbasids did including the name of the caliph and other state functionaries become standard.