Bamiyan (central Afghanistan) is a Buddhist establishment in the western part of the Hindu Kush range. It is composed of a number of monasteries, temples and cave complexes – totalling over 900 individual structures – carved into the rock of the cliffs bordering the Bamiyan valley (Fig. A) and the minor adjacent valleys of Kakrak and Fola Deh.

The Buddhist kingdom of Bamiyan was visited by the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang in 628/29 CE. From his account it is possible to infer the political and economical power of this kingdom, and also of the Buddhist establishment there, which had taken roots around the mid 6th century CE when the long-distance trade routes between Central Asia and India shifted to lead direct through Bamiyan. The prosperity of the kingdom, at its apex in the 7th–8th century, declined in the 9th / 10th century with the progressive islamisation of the region. This chronology is consistent with the art historical evidence provided by the lavishly painted and sculpted decoration of some of the caves and their overall features. Square or octagonal in plan, the decorated caves have vaulted or “lantern-roofed” ceilings and are believed to reproduce architectural forms of the time.

Unlike other rock-cut temples of the period, both in India and Central Asia, the Bamiyan caves do not contain a central cult object; rather the iconographic programmes are organised around a vertical axis and centred on the vault, which represents both the physical and conceptual zenith where the celestial dimension is evoked.

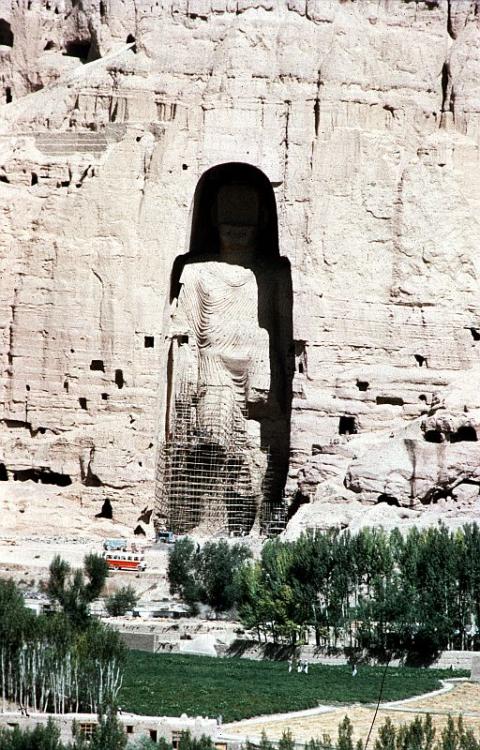

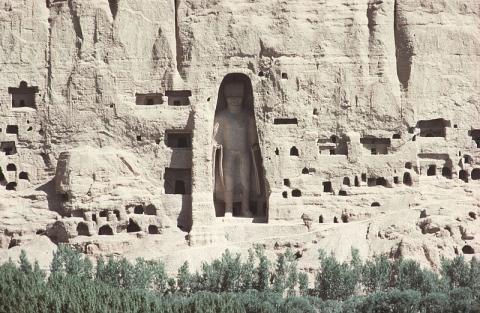

However, Bamiyan owes its fame to two colossal Buddha images (55 and 38 m high; Figs. B, C), which were blasted to rubble by the Taliban in 2001. The statues and their niches, carved in high relief out of the rock, were situated about 500 m apart at the western and eastern ends of the main valley’s larger cliff. They were supposed to represent Dīpamkara and Śākyamuni, the first and the last historical Buddhas. According to Xuanzang’s account, there was a third colossal reclining statue representing the Buddha at the moment of his 'death', or the crucial moment when, through physical death, he enters nirvāṇa, the blissful condition following the total extinction of physical and spiritual individuality. No traces have been found of this third colossus, perhaps already worn away by natural erosion. Other, smaller colossal statues were probably housed in the now empty niches; their appearance would have been similar to that of the 7.70 m high standing Buddha preserved in the Kakrak Valley.

Among the paintings in Bamiyan those in the niches of the colossal Buddha statues have become the most famous. Special mention must be made of the solar deity on a chariot pulled by four horses and accompanied by minor divine characters on the ceiling of the niche of the 38 m Buddha as well as a ceremonial scene with royal personages and bejewelled Buddhas on the upper part of the niche. On the ceiling and upper part of the niche surrounding the 55 m Buddha, a complex scene, of which unfortunately the central part is missing, contains celestial beings, bodhisattvas and a bejewelled Buddha.

The ceremonial scene depicted in the niche of the 38 m Buddha is probably the iconographic translation of actual ceremonies of great religious and political relevance which, Xuanzang reported, were periodically performed at Bamiyan. On this occasion, in front of a large audience the local ruler symbolically divested himself of his riches on behalf of the Buddha, thus implicitly asserting his legitimate sovereignty.

In light of the damages suffered in the recent iconoclastic attack, local and international teams of scientists are currently working at Bamiyan. Their efforts concentrate mainly on the consolidation of the rocks damaged in the explosions, analysis of the paintings, attempts at restoring the destroyed colossal statues (physically or virtually), and archaeological investigations aimed at localising the “western monastery” and the vestiges of the town mentioned by Xuanzang. .