In the rabbinical literature that reflects the thoughts and paths of the Jewish people under Roman rule, continuous shifts can be traced in Jewish attitudes towards images. Iconographic elements of the pagan (religious) world were adopted during this period and employed both privately and publicly, for instance in synagogues.

Palestine After the Second Jewish War

Following the Second Jewish War, the currency supply in Palestine was primarily provided by the major urban centres such as Aelia Capitolina, Neapolis and Caesarea Maritima. In their coinage, the Roman pictorial language completely replaced older Jewish traditions, even in those cases where reference is made to local customs.

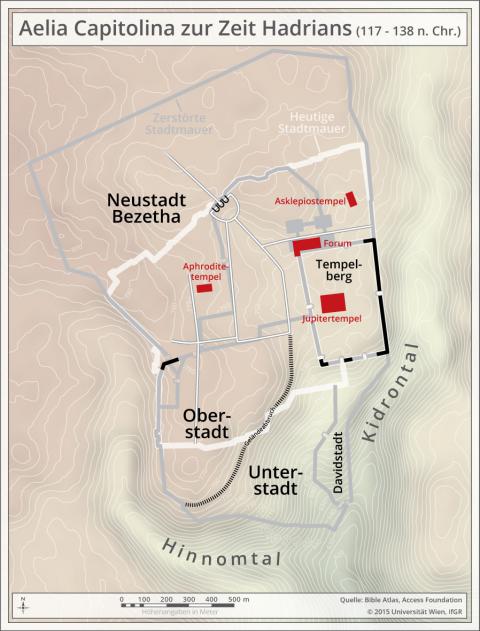

Aelia Capitolina: Coins that depict the emperor engaged in ritual ploughing of the outer borders of the new settlement illustrate that the foundation of the colony Aelia Capitolina can be traced to Hadrian (No.1A). According to Roman religious law, the re-foundation was effected by marking the city boundaries with a plough pulled by a cow and a bull. The emphasis of the status as colonia continued in the coinage after Hadrian (No.2A), and the temple of Jupiter also remained prominently depicted (No.3B).

Neapolis: The city of Neapolis was founded by Vespasian after the First Jewish War at the foot of Mount Gerizim. As in Jerusalem, Hadrian also had a temple to Jupiter or Zeus erected on the mountain there, which was a central motif in the Roman currency of the city and simultaneously an unusual depiction of landscape in Palestinian coinage (No.4A). The city issued its own coins until the third century. The pagan imagery, introduced from the period of Antonius Pius (138 – 161 CE), is unmistakeable (No.5B).

Caesarea Maritima: The Roman seat of government at Caesarea Maritima was re-established by Emperor Vespasian following the First Jewish War as a colony named Colonia Prima Flavia Augusta Caesarea. The foundation of the colony continued to be emphasized in the coinage of Hadrian (No.7A). References to the harbour complex originally constructed by Herod the Great were also kept in later coins (No.8B).

In the numismatic material from the period after the Second Jewish War, it is no longer possible to identify iconographic elements that can be attributed to a specifically Jewish context. On one hand, this is the result of the destruction of Jewish power structures, but it also represents an increased acceptance of all types of iconographic depiction. The rabbinical literature documents this change in Jewish attitudes toward figural representation. In the Genesis Rabba – a midrash (biblical interpretation) edited during the fifth century CE – there is a short report which lists coins showing biblical protagonists, including the patriarchs Abraham, Joshua, and David and the prophet Mordecai. This clearly refers to coins depicting Roman emperors. The Jewish reading that the images presented the life and times of Abraham made the iconography more acceptable to the Jews. This more permissive position towards figural representation allowed a pragmatic treatment of pagan iconography.

Further Reading

Y. Meshorer et al., Coins of the Holy Land. The Abraham and Marian Sofaer Collection at the American Numismatic Society and the Israel Museum, New York 2013, 2 vols.

P. Schäfer, Geschichte der Juden in der Antike. Die Juden Palästinas von Alexander dem Großen bis zur arabischen Eroberung, Tübingen 2010

![Bust of Hadrian with laurel wreath, draped; Latin: [IMP] CAES TRAIANO [HADRIANO AVG PP] (to Imperator Caesar Traian Hadrian Augustus Pater Patriae) Bust of Hadrian with laurel wreath, draped; Latin: [IMP] CAES TRAIANO [HADRIANO AVG PP] (to Imperator Caesar Traian Hadrian Augustus Pater Patriae)](../sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/coins/16_01A_1.png%3Fitok=h-0n2S2u)

![Bust of Hadrian with laurel wreath, draped; Latin: [IMP] CAES TRAIANO [HADRIANO AVG PP] (to Imperator Caesar Traian Hadrian Augustus Pater Patriae) Bust of Hadrian with laurel wreath, draped; Latin: [IMP] CAES TRAIANO [HADRIANO AVG PP] (to Imperator Caesar Traian Hadrian Augustus Pater Patriae)](../sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/coins/16_01B_1.png%3Fitok=Y_IZwsJy)